Table of contents

From generation to generation: What we (don't) want to inherit from our mothers

And suddenly I hear myself saying: "Just like my mother." Sometimes with a smile. Sometimes with a slight fright. Because there is often a whole legacy between the things we love and the things we consciously want to do differently. An emotional, psychological, cultural legacy.

This text is an invitation to reflect on how motherhood, femininity and self-image are passed down through generations. And about what we want to keep, change or lovingly let go of.

What remains: love, strength, devotion

Many of us grew up with women who made the impossible possible. Who worked, raised, nurtured, organized and loved - often all at the same time. Mothers who didn't ask if they could still do it. They just did it. Her power was self-evident - her presence sometimes too.

In depth psychology we speak of “implicit transferences”: unconscious attitudes that we take over from our parents. The way we approach conflict. How we show care. How we allow closeness. All of this was shaped before we consciously decided.

Attachment theorists such as John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth have shown that early childhood attachment experiences not only shape the relationship with the mother, but also influence all later attachment behavior. Those who were seen, heard and regulated in early childhood can often allow healthy closeness as adults - or give it to others. This emotional legacy is valuable. And it can be passed on.

And yet there are things that feel like a warm coat: the little rituals, the snack, the look that said: I believe in you. These impressions can remain. Maybe not one on one. But at the core. And they show us: It wasn't just what our mothers did that shaped us - but how they thought, felt and loved. We'll pass that on too.

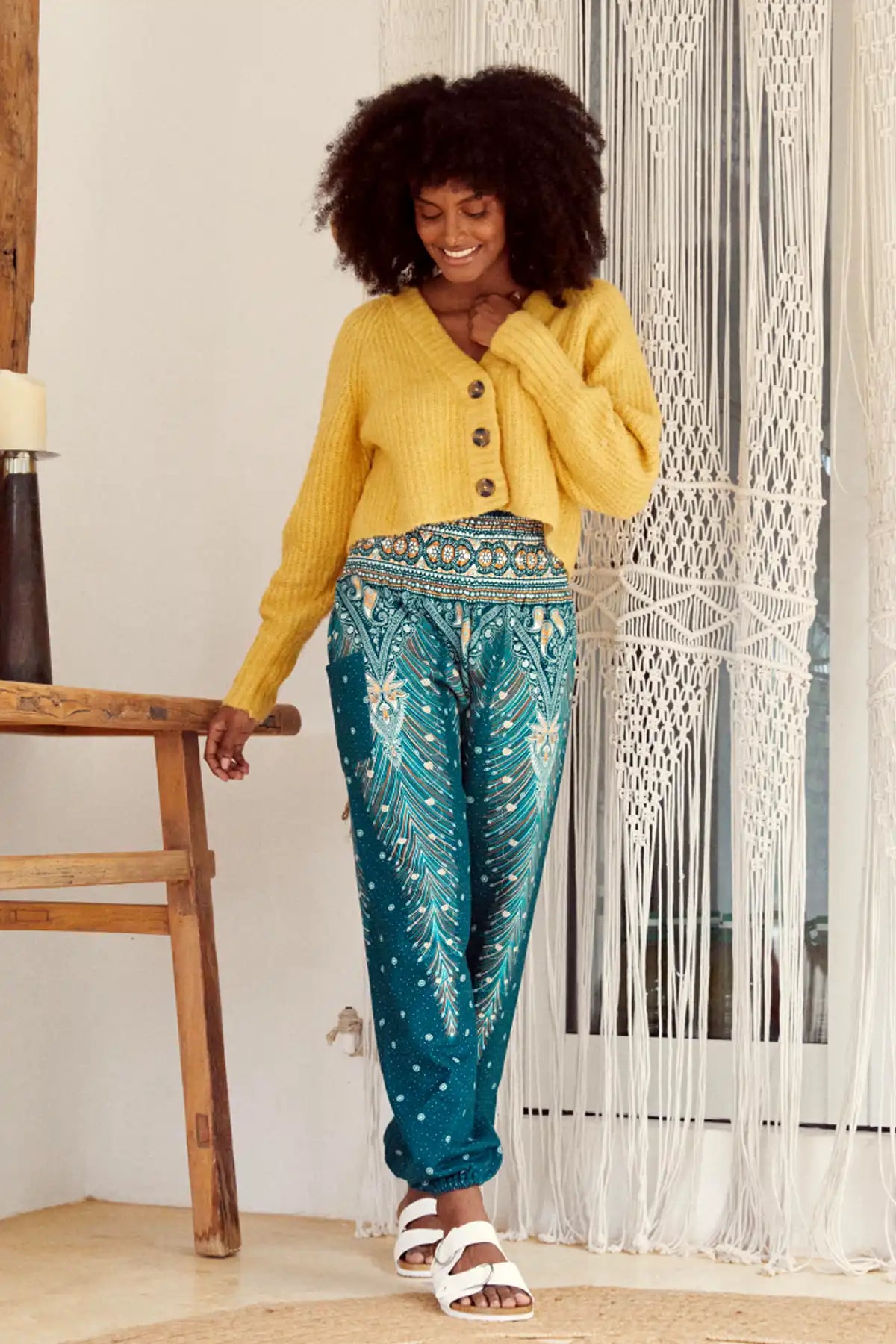

Picture: Kristina Paukshtite / pexels

What we can let go of: exhaustion, self-sacrifice, silence

Our mothers – and their mothers – carried a lot. And a lot secretive. Trauma, structural inequality, emotional injuries. In many families it was common practice to ignore the pain. To function. To be strong – whatever the cost.

Transgenerational psychology, researched by experts such as Marianne Leuzinger-Bohleber, Sabine Bode and Judith Herman, shows that topics that have not been dealt with are often passed on unconsciously. As fear, as guilt, as vague pressure. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu described this phenomenon as “incorporated inheritance” – we carry social and emotional structures in our bodies, our language, our behavior.

Anyone who feels tired today, for no reason, may be carrying the fatigue of generations. The body remembers even when the mind cannot find words. Trauma research (e.g. Bessel van der Kolk) shows: Unprocessed experiences are stored in the nervous system - and often repeated in the next generations.

We can break the pattern. We can say no. To be tired. Ask questions. And no longer accept sentences like “That’s just how it was back then” as justification. Setting boundaries isn't a betrayal - it's a new form of love.

Mother's role in transition: between ideal and reality

A lot has changed in public perception. “Attachment parenting” and “selfcare”, mental health and feminist motherhood – these are all new narratives that create space for individual paths. And yet we often find ourselves caught between two chairs: the unconditionally giving mother of the past and the ideal of the constantly reflective super mom of today.

The field of tension is great. Many mothers today expect to be emotionally available, educationally competent, professionally committed, physically present and as calm as possible. Psychology speaks here of “mental load” – the invisible burden that comes with responsibility for family and maintaining relationships. Sociologists like Gabriele Winker and authors like Patricia Cammarata have been drawing attention for years to the fact that care work must be socially visible and distributed fairly - beyond a romanticized image of the mother.

Sometimes what we lack is permission to be imperfect. Ambivalent. Contradictory. Mothers who cry, are angry, doubt - and still love. The new generation can make visible what has long been hidden. And there is power in that. Because there is humanity in ambivalence. The psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott spoke of the 'good enough mother' - not perfect, but sensitive enough. One that can also fail.

What we can give ourselves

In the end, it's not just about what we accept or reject. It's about self-responsibility. To consciously recognize: What is mine? What has been learned? What can heal?

In systemic therapy it is often said: "Those who understand their origins can lead their own lives." Maybe it's the loving look at your own mother - not idealizing, not accusing, but understanding. Or it is the moment in which we tell our inner child: You can do it differently.

Or it’s the conversation we’re having today – honest, vulnerable, connected. Because the greatest gift we can give is not perfection. But awareness. And compassion.

What we inherit from our mothers is not a set plan. It is a range of possibilities. And we can choose. What we pass on doesn't just start with the next child. It starts with looking at ourselves.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.