Inhaltsverzeichnis

From generation to generation: what we want to do from our mothers (not)

And suddenly I hear myself saying: "Just like my mother." Sometimes with a smile. Sometimes with a slight shock. Because between the things we love and those we consciously want to do differently, there often lies an entire legacy. An emotional, psychological, cultural legacy.

This text is an invitation to reflect—on how motherhood, femininity, and self-image are passed down through generations. And on what we want to keep, change, or lovingly let go of.

What remains: love, strength, devotion

Many of us grew up with women who made the impossible possible. They worked, raised, cared, organized, and loved—often all at once. Mothers who didn't ask if they could still do it. They simply did it. Their strength was taken for granted—and sometimes their presence, too.

In depth psychology, we speak of "implicit transferences": unconscious attitudes we adopt from our parents. The way we approach conflicts, the way we show care, the way we allow closeness. All of this was shaped before we consciously decided to do so.

Attachment theorists such as John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth have shown that early childhood attachment experiences not only shape the relationship with the mother, but also influence all subsequent attachment behavior. Those who were seen, heard, and regulated in early childhood are often able to allow healthy closeness as adults—or give it to others. This emotional legacy is valuable. And it can be passed on.

And yet there are things that feel like a warm blanket: the little rituals, the packed lunch, the look that said, "I believe in you." These influences are allowed to remain. Maybe not exactly. But at their core. And they show us: It wasn't just what our mothers did that shaped us—but how they thought, felt, and loved. We pass that on, too.

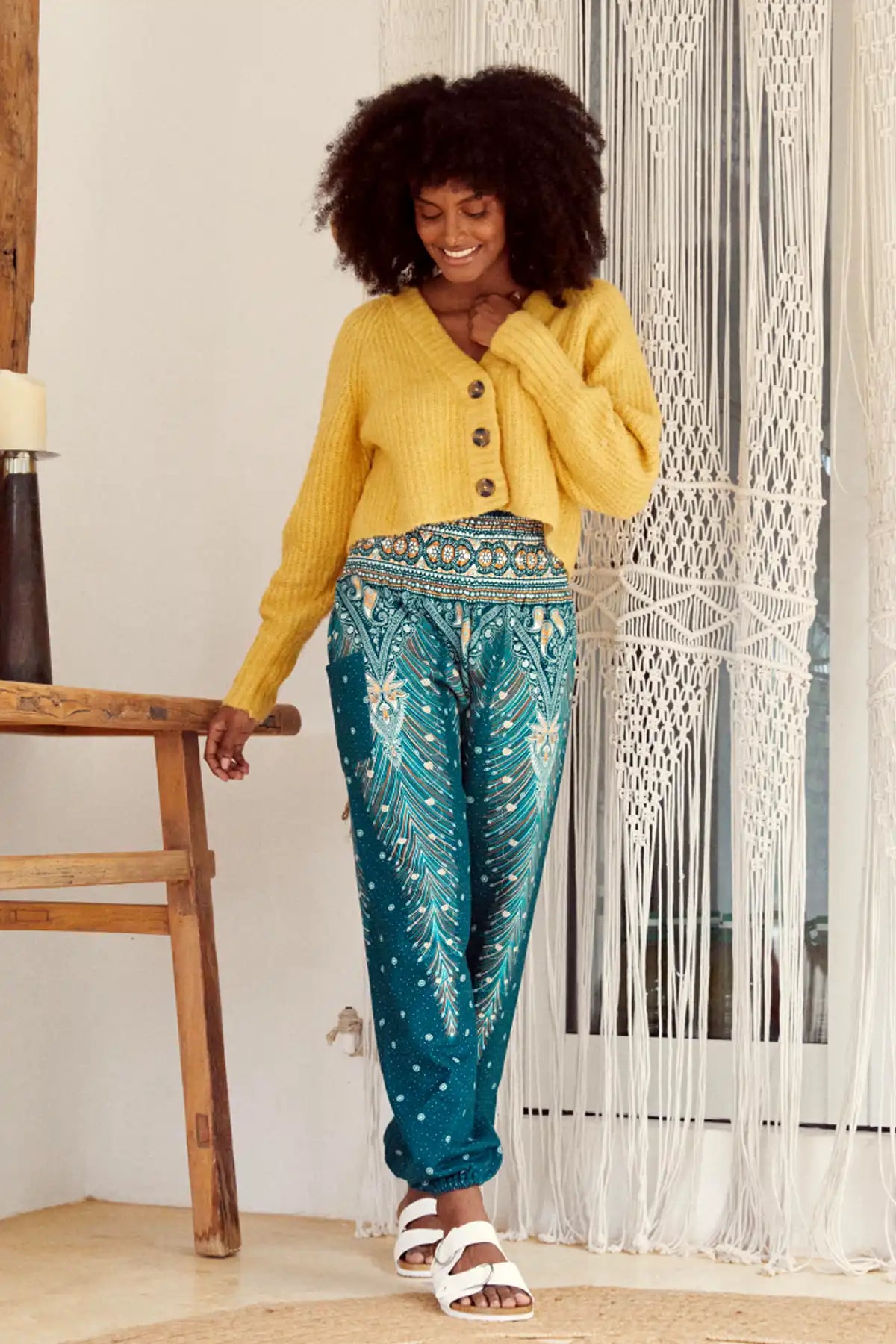

Picture: Kristina Paukshtite/pexels

What we can let go of: exhaustion, self-abandonment, silence

Our mothers—and their mothers—carried a lot. And kept a lot secret. Trauma, structural inequality, emotional wounds. In many families, it was common to ignore the pain. To function. To be strong—no matter the cost.

Transgenerational psychology, researched by experts such as Marianne Leuzinger-Bohleber, Sabine Bode, and Judith Herman, among others, shows that unresolved issues are often passed on unconsciously. As fear, as feelings of guilt, as vague pressure. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu described this phenomenon as "incorporated inheritance"—we carry social and emotional structures in our bodies, our language, our behavior.

Anyone who feels tired today, for no reason, may be carrying the exhaustion of generations. The body remembers, even if the mind can't find the words. Trauma research (e.g., Bessel van der Kolk) shows that unprocessed experiences are stored in the nervous system—and often repeated in subsequent generations.

We're allowed to break the pattern. We're allowed to say no. Be tired. Ask questions. And stop accepting phrases like "That's just how it was back then" as justification. Setting boundaries isn't betrayal—it's a new form of love.

Mother's role in transition: Between ideal and reality

Much has changed in public perception. "Attachment parenting" and "self-care," mental health and feminist motherhood—all these are new narratives that create space for individual paths.And yet we often find ourselves caught between two stools: the unconditionally giving mother of the past and the ideal of the constantly reflective super mom of today.

The tension is immense. Many mothers today are expected to be emotionally available, educationally competent, professionally engaged, and physically present, while remaining as calm as possible. Psychology refers to this as the "mental load" – the invisible burden that comes with the responsibility for family and maintaining relationships. Sociologists such as Gabriele Winker and authors such as Patricia Cammarata have been pointing out for years that care work must be socially visible and fairly distributed – beyond a romanticized image of motherhood.

What we sometimes lack is the permission to be imperfect. Ambivalent. Contradictory. Mothers who cry, are angry, doubt—and still love. The new generation is allowed to make visible what has long been hidden. And therein lies strength. For humanity lies in ambivalence. The psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott spoke of the 'good enough mother'—not perfect, but sensitive enough. One who is also allowed to fail.

What we can give ourselves

In the end, it's not just about what we accept or reject. It's about personal responsibility. About consciously recognizing: What is mine? What have we learned? What can heal?

In systemic therapy, it's often said: "Those who understand their origins can lead their own lives." Perhaps it's the loving gaze toward one's own mother—not idealizing, not accusing, but understanding. Or it's the moment when we tell our inner child: You're allowed to do things differently.

Or it's the conversation we're having today—honest, vulnerable, connected. Because the greatest gift we can give isn't perfection. It's awareness. And compassion.

What we inherit from our mothers isn't a fixed plan. It's a spectrum of possibilities. And we're free to choose. What we pass on doesn't begin with the next child. It begins with how we look at ourselves.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.